Chapter 15 Security of Payment Legislation New South Wales

Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 1999 (NSW)

The security of payment legislation in NSW is governed by the:

- Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 1999 (NSW) (NSW Act)

- the Contractors Debts Act 1997 (NSW) (NSW Debts Act).

When does the legislation apply?

Contracts entered into before 21 October 2019 are governed by the unamended provisions of the NSW Act.

The NSW Act (as amended) applies to contracts entered into on or after 21 October 2019.

The NSW Act applies to any contract or other arrangement (that gives rise to a legally binding obligation, although it need not be contractual in nature) to carry out construction work or supply related goods and services within New South Wales (construction contract). There is no requirement for the contract or arrangement to be in writing. It can be written or oral, or a combination of both.

‘Construction work’ is defined very broadly and exclusions are essentially limited to mining operations. It includes construction, alteration, repair, maintenance and demolition of most structures that can be fixed to land. Accordingly, the NSW Act will apply to most typical construction contracts and consultancy agreements.

The NSW Act does not apply to a construction contract:

- that forms part of a loan agreement, a contract of guarantee or a contract of indemnity;

- for residential building work if the owner lives or intends to live in the building (see Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Regulation 2008 – Reg 3A);

- where it is agreed that the consideration payable is not calculated by referring to the value of the work carried out or the goods and services supplied;

- under which a party undertakes to carry out construction work, or supply related goods and services, as an employee; and

- to the extent the construction work or related services are carried out outside NSW.

CASE STUDY

Lendlease Engineering Pty Ltd v Timecon Pty Ltd [2019] NSWSC 685

Facts

- The unincorporated joint venture formed by Lendlease Engineering Pty Ltd and Bouygues Construction Australia Pty Ltd (LLBJV) was the head contractor on the NorthConnex motorway project in Sydney.

- LLBJV was the respondent to an adjudication application made by Timecon relating to the disposal of tunnel spoil to a site in Somersby, NSW.

- LLBJV commenced proceedings to have an adjudication determination in Timecon’s favour set aside on the basis of jurisdictional error, on the basis that there was no ‘contract or other arrangement’ between it and Timecon.

- Timecon had argued that the ‘other arrangement’ was constituted by pre-contractual conversations and emails with LLBJV regarding the proposed delivery of spoil to the site.

- LLBJV agreed that it had deposited spoil at the site, however, this was under an agreement it had made with a third party, Laison Earthmoving Pty Ltd.

Result

- The NSW Supreme Court held that there was no ‘contract or other arrangement’ between LLBJV and Timecon. Accordingly, the adjudication determination was set aside.

- Although previous case authority suggested that the ‘other arrangement’ did not need to be legally binding, having regard to the purposive nature of section 32 of the NSW Act, the relevant arrangement must give rise to a legally binding obligation, although it need not be contractual in nature (eg an equitable obligation).

- The Court said that ‘the purpose of the SOP Act is not to create an obligation to pay where one does not exist’.

The NSW Act applies even if the construction contract specifies that it is governed by the law of another jurisdiction.

Contracts cannot include a ‘pay when paid‘ provision, which is where a contractor makes its liability to pay a subcontractor dependent on payment to the contractor by a principal. For example, this includes making payment of retention dependent on achievement of practical completion under the head contract.

It is not possible to exclude the operation of the NSW Act in any construction contract to which it applies.

What rights does the legislation give to contractors?

When can contractors make a claim?

A claim for a progress payment (payment claim) can only be made on or from:

- the last day of the named month in which construction work was first carried out and the last day of each subsequent named month; or

- an earlier date specified in the contract in any particular named month; and

- if the contract has been terminated, the date of termination.

Importantly, unless the construction contract provides otherwise, only one payment claim may be served in any particular named month for construction work carried out or undertaken to be carried out in that month.

A payment claim cannot be made 12 months after the construction work is finished or related goods and services to which the claim relates were last supplied, unless the construction contract provides for a later period.

A corporation in liquidation cannot make a payment claim or take action to enforce a payment claim or an adjudicator’s determination in respect of a construction contract entered into on or after 21 October 2019.

How does a contractor make a payment claim?

A claimant makes a payment claim by serving the payment claim on the person who is liable to make the payment under the construction contract (respondent).

A payment claim must:

- identify the construction work or related goods and services;

- indicate the amount of the progress payment the claimant claims to be due (claimed amount); and

- state that it is made under the NSW Act.

The requirement that a payment claim state that it is made under the NSW Act only applies to payment claims made in respect of construction contracts entered into on or after 21 October 2019.

If the claimant is a head contractor, being a person who carries out construction work for a principal and for whom construction work is carried out as part of or in addition to the work the head contractor performs for the principal, then the claimant must also include with the payment claim a supporting statement in the form required by the regulations to the NSW Act. The supporting statement requires the head contractor to state that it has paid its subcontractors amounts then due.

While claimants must strictly adhere to the requirements of the NSW Act, courts will look past technicalities to avoid setting aside an adjudicator’s determination.

CASE STUDY

Modog Pty Ltd v ZS Construction (Queenscliff) Pty Ltd [2019] NSWSC 1743

Facts

- The head contractor, ZS Construction (Queenscliff) Pty Ltd (Queenscliff) issued to the developer Modog Pty Ltd (Modog) an email attaching a ‘payment summary sheet’, followed by six further emails which attached invoices from Queenscliff itself for project management services, plus invoices from third party suppliers/trades.

- Queenscliff had taken a similar approach during the course of the contract.

- Modog issued multiple payment schedules which scheduled $Nil.

- At adjudication and the adjudicator determined that Queenscliff was entitled to payment for some of the invoices.

- Modog applied to set aside the adjudicator’s determination, arguing that the email attaching the payment summary sheet was not valid payment claim under the NSW Act as it did not expressly claim payment.

- Modog argued that the adjudicator did not have jurisdiction to determine multiple payment claims in respect of a single reference date and, therefore, the adjudicator’s determination that the invoices should be paid was made in error.

Result

- Modog’s application was dismissed because Queenscliff had submitted one payment claim ‘when viewed as a matter of substance rather than form’.

- The parties’ past dealings were relevant in determining that the summary payment sheet and invoices should be read together to constitute the one payment claim.

What type of payments are excluded?

No type of payments are expressly excluded from being claimed. However, the payment claim must only include payment for construction work under the contract. Unless the contract expressly makes provision for the payment of damages for breach, they are not claimable in a payment claim.

What must a respondent do when faced with a claim?

Respondent to serve payment schedule

If a respondent is served with a payment claim, it must respond by serving the claimant with a payment schedule setting out the amount that the respondent proposes to pay.

When to serve a payment schedule

The respondent must serve the payment schedule within 10 business days of receiving the payment claim or any shorter time that is stated in the contract.

What must be included in the payment schedule?

To comply with the NSW Act, the payment schedule must:

- identify the relevant payment claim;

- indicate the amount (if any) the respondent proposes to pay (scheduled amount); and

- if the scheduled amount is less than the claimed amount, explain why and any reasons for withholding.

What amount must be paid?

If the respondent does not provide a payment schedule within the time limit, it must pay the full amount of the payment claim.

If the respondent does provide a payment schedule, it must pay the scheduled amount.

When is payment due?

A progress payment by a principal to a head contractor becomes due and payable:

- 15 business days after service of the payment claim; or

- on such earlier date as provided by the construction contract.

A progress payment by a head contractor to a subcontractor becomes due and payable:

- 30 business days after service of the payment claim for a construction contract entered into before 21 October 2019; or

- 20 business days after service of the payment claim for a construction contract entered into on or after 21 October 2019; or

- on such earlier date as provided for in the construction contract.

A principal is a person for whom construction work is carried out who themselves are not engaged under a construction contract.

A subcontractor is someone who is engaged to perform construction work who is not a head contractor.

A progress payment to a subcontractor in connection with an owner occupier construction contract for residential building work under the Home Building Act, where the owner lives or intends to live in the house, is due and payable:

- on a date determined in accordance with the construction contract; or

- if the contract makes no express provision, 10 business days after the service of the payment claim.

Right to interest on unpaid amount

Interest is payable on the unpaid amount of any progress payment at whichever rate is the greater of:

- the rate prescribed under section 101 of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW); or

- the rate specified under the construction contract.

Defences to the consequences of failing to provide a payment schedule

The case study below demonstrates that a respondent can raise misleading and deceptive conduct as a possible defence to the consequences of failing to provide a payment schedule within the relevant timeframe as a result of that misleading and deceptive conduct.

CASE STUDY

Bitannia Pty Ltd & Anor v Parkline Constructions Pty Ltd [2006] NSWCA 238

Facts

- Parkline Constructions served a payment claim on Bitannia.

- Bitannia did not provide a payment schedule within the time limit specified in the NSW Act which resulted in it being liable for the full payment claim.

- The delay was attributed to the fact that Parkline Constructions had sent the claim to the general manager of Bitannia’s associated company, rather than the architect responsible for payment claims.

- A message attached to the payment claim stipulated that it related to ‘retention release and variations as previously forwarded to [the architect]’, indicating that the architect was also in possession of the relevant claim at that point in time.

Result

The New South Wales Court of Appeal held that:

- the NSW Act does not require a payment claim to be served in good faith; and

- the NSW Act allows a party to raise a defence to the consequences of failing to provide a payment schedule under section 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (now section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law) asserting that the misleading and deceptive conduct of the claimant contractor prevented submission of the payment schedule within the prescribed time limit.

- See also A-Tech Australia Pty Ltd v Top Pacific Construction Aust Pty Ltd [2019] NSWSC 404 (as a state law cannot exclude a defence arising under a Commonwealth law).

Contractor’s rights if not paid – how to enforce its rights

Obtaining a judgment

The claimant may enforce its right to a progress payment by applying to the court for judgment in the amount of:

- the payment claim, where the respondent fails to serve a payment schedule in accordance with the NSW Act; or

- any unpaid scheduled amount which remains unpaid on the due date for payment.

Right to lien

A claimant may exercise a lien over any unfixed plant or materials which the claimant has supplied for use in the construction work for the respondent, where a progress payment becomes due and payable but remains unpaid.

Right to suspend work

A claimant may suspend construction work being carried out or related goods and services being supplied (with at least 2 business days’ notice). The respondent becomes liable for any loss or expenses incurred by the claimant in connection with the work under the contract during the period of suspension.

Adjudication

How and when to make an adjudication application

A claimant can apply for adjudication of the payment claim within:

- 10 business days after the claimant receives the respondent’s payment schedule, if the scheduled amount is less than the claimed amount; or

- 20 business days after the due date for payment, if the respondent has failed to pay the whole or any part of the scheduled amount.

If the respondent has failed to provide a payment schedule in accordance with the NSW Act, the claimant is also entitled to apply for an adjudication as long as it follows the following steps:

- within 20 business days after the due date for payment, serve a written notice on the respondent of its intention to submit an adjudication application;

- the notice must allow the respondent 5 business days to provide a payment schedule; and

- then, after that 5-day period, and within 10 business days, the claimant may apply for adjudication.

In addition to the requirements for service within the specified times described above, the adjudication application must:

- be in writing;

- be made to a nominating authority authorised under the NSW Act to nominate an adjudicator;

- identify the payment claim to which it relates;

- identify the payment schedule to which it relates, if any;

- be accompanied by the authorised nominating authority’s application fee, if any; and

- be copied to the respondent.

A claimant may include submissions with the adjudication application; however, this is not a necessary requirement of the NSW Act.

The adjudication application must as soon as practicable be referred by the authorised nominating authority to an adjudicator. The adjudicator must then notify the parties of acceptance of the adjudication application.

An adjudication application can be withdrawn by the claimant. If an adjudicator is yet to be appointed, or has been appointed but has not yet made a determination, the application can be withdrawn at any time. If the adjudicator has been appointed, the withdrawal does not have effect if the respondent objects to the withdrawal and the adjudicator considers that it is in the interests of justice to uphold the objection.

How to respond to an adjudication application

The respondent must lodge its adjudication response by the later of:

- 5 business days after receiving the adjudication application; or

- 2 business days after receiving notice that the adjudicator has accepted the adjudication application.

The adjudication response:

- may only be lodged if the respondent issued a payment schedule within the time allowed in the NSW Act;

- must be in writing;

- must identify the adjudication application to which it relates; and

- may contain submissions relevant to the response, as long as any reasons for withholding payment were previously raised in its payment schedule.

When will the adjudicator make his or her determination?

The adjudicator must determine the adjudication application within 10 business days after:

- if an adjudication response is lodged, the date on which the respondent lodged the adjudication response;

- if no adjudication response is lodged, the end of the period within which the respondent was entitled to lodge a response;

- in any other case, the date on which the adjudicator accepted the application was served on the parties; or

- an extended timeframe agreed by the parties.

The adjudicator is required to determine:

- the amount of the progress payment to be paid (adjudicated amount);

- the date on which the adjudicated amount becomes payable; and

- the rate of interest on the adjudicated amount.

In making a determination, an adjudicator can only consider the following matters:

- the provisions of the NSW Act;

- the provisions of the relevant construction contract;

- the payment claim, together with all submissions and relevant documentation in support of the claim;

- any payment schedule, together with all submissions and supporting documentation;

- the adjudication application;

- the adjudication response; and

- the results of any inspection carried out by the adjudicator.

The adjudicator’s determination must be in writing, include reasons for the determination and be served on the parties. However, if both parties agree, the claimant and the respondent may request the adjudicator not to include reasons in the determination.

When is payment due?

The respondent must pay that adjudicated amount within 5 business days of the respondent receiving the determination from the adjudicator, or a later date as determined by the adjudicator.

Consequences of failing to pay the adjudicated amount

If the respondent fails to pay the whole or any part of the adjudicated amount, the claimant may request an adjudication certificate from the ANA and then file the adjudication certificate as a judgment debt in a court. The claimant may also suspend the carrying out of construction work after 2 business days’ notice to the respondent.

Challenges to the adjudicator’s determination

There are very limited avenues to appeal a determination. If a party wishes to have a determination set aside, it will need to apply to the Supreme Court. If the court makes a finding that a jurisdictional error has occurred in relation to an adjudicator’s determination, the court may make an order setting aside the whole or any part of the determination. The court may identify the part of the adjudicator’s determination affected by jurisdictional error and set aside that part only, while confirming the part of the determination that is not affected by jurisdictional error.

Payment withholding requests

What is a payment withholding request?

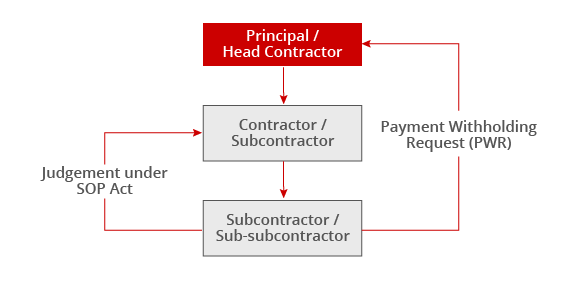

To explain the concept of a payment withholding request (PWR), we have assumed a basic contractual chain of principal, contractor and subcontractor, though the PWR scheme would equally apply in the scenario of head contractor, subcontractor and sub-subcontractor.

A claimant/subcontractor is entitled to serve a PWR on a principal at the same time it serves an adjudication application on the respondent/contractor.

Upon receiving a PWR, the principal must withhold from any amount payable or that becomes payable to the respondent/contractor which includes an amount in respect of the work done/services provided by a claimant/subcontractor, an amount commensurate to that claimed by the claimant/subcontractor. If the principal fails to comply with this request, it will become jointly and severally liable with the respondent/contractor for the amount owed to the claimant/subcontractor.

Who’s who in the contractual chain and what is a ‘Principal Contractor’?

The scheme is designed to work anywhere up and down the contractual chain, and therefore the obligations on a contractor would vary depending upon where that contractor sits in relation to the party entitled to issue the PWR. The basic contractual chain is illustrated in the below diagram:

The term Principal Contractor in the scheme does not have the typical meaning that is understood in the industry in relation to WHS obligations on site (see Chapter 16). It defines the entity or individual liable to the respondent for work carried out or materials supplied by the respondent as part of, or incidental to, the work or materials that the respondent engaged the claimant to carry out or supply.

What are the requirements of a PWR?

The PWR must:

- be served by a claimant/subcontractor who has made an adjudication application for a payment claim;

- be in the form approved by the NSW Fair Trading Commissioner; and

- include a written statutory declaration that the claimant genuinely believes that the amount of money claimed is owed by the respondent.

What to do if you are served with a PWR

Upon receipt of a PWR, the Principal Contractor must retain out of money that is or becomes payable:

- the money owed by it downstream to its immediate subcontractor (which is the respondent in the adjudication), the amount of money to which the payment claim relates; or

- if the amount of money owed by the Principal Contractor is less than the amount to which the claim relates, retain that amount.

If a part payment has been made in respect of the payment claim, the Principal Contractor is only required to retain money to the value of the balance of the payment claim.

However, if a person in receipt of a PWR is not (or is no longer) the Principal Contractor, that person must give notice of this to the claimant within 10 business days after receiving the PWR. Penalty units apply for breach of this provision.

A person may no longer be a Principal Contractor as a result of money owed to the respondent having been paid before the PWR was served, assuming that evidence of payment can be established.

There is no obligation under the NSW Act on the Principal Contractor to pay the amount retained to the claimant/subcontractor. If the subcontractor wants to receive payment if it is successful in the adjudication and is unable to recover the adjudicated amount from the respondent/contractor, it must issue a notice of claim under the NSW Debts Act as described below.

Notification requirements

An adjudicator may order, at the request of a subcontractor, that a contractor provide the necessary details of the Principal Contractor to the subcontractor. Penalty units apply for failure to provide this information.

A subcontractor does not need to notify a contractor that it has issued a PWR on a Principal Contractor. A contractor should therefore be mindful of the risk that a significant PWR could have upon its forecast cash flow in a project and perhaps consider imposing an obligation on the subcontractor to notify it of any PWRs in the relevant subcontract.

Personal Liability

The NSW Act contains personal liability provisions against directors and management for certain offences.

Directors and managers can be held personally liable:

- for offences committed by a corporation under the NSW Act if they are a director of the corporation or involved in the corporation’s management and in a position of influence over the corporation’s conduct in relation to the offence under the NSW Act;

- if they are knowingly concerned in the commission of the offence under the NSW Act of the corporation by aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring the commission of the corporation’s offence, inducing the corporation’s offence, or conspiring to effect the corporation’s offence;

- if they know the offence would be committed, is being committed, or are recklessly indifferent as to whether it would be or is being committed, and fail to take all reasonable steps to prevent or stop the commission of the offence.

To avoid liability, directors and managers can take measures including assessing and undertaking regular professional assessments of compliance, and providing information, training, instruction and supervision to enable compliance, implementing structures, work systems and processes to support compliance, and creating a corporate culture that does not encourage or tolerate non-compliance.

Penalties

A summary of penalties for offences under the NSW Act are listed in Schedule 3 of the Building Industry Security of Payment Regulation 2008. One penalty unit equates to $110.

Code of practice for authorised nominating authorities

Authorised Nominating Authorities (ANAs) are people authorised by the Minister to nominate individuals to determine adjudication applications. The NSW Act permits the Minister to make a code of practice which must be observed by ANAs. From 1 January 2021, all ANAs must adhere to the Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment – Authorised Nominating Authorities (Code of Practice) Order 2020. The Code sets out the standards to which ANAs must carry out their functions.

Amendments to the legislation

In November 2018, changes to the NSW Act were introduced through the Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Amendment Act 2018 (Amendment Act) and commenced on 21 October 2019. The new provisions only apply to construction contracts entered into on or after 21 October 2019. The changes have been incorporated in this Chapter.

Contractors Debts Act 1997 (NSW) (NSW Debts Act)

When does the legislation apply?

The NSW Debts Act applies when a person (unpaid person) is owed money by another person (defaulting contractor) for work carried out for or materials supplied by the unpaid person to satisfy the obligations of the defaulting contractor to some other person (principal). The Act expressly provides that the term ‘carrying out of work’ incorporates construction work under a construction contract, within the meaning of the NSW Act. It is not possible to contract out of the NSW Debts Act.

What rights does the legislation confer on contractors?

Right of assignment of debt from principal

The NSW Debts Act gives an unpaid subcontractor the right to require the assignment to it of the principal’s obligation to pay money it owes under the head contract to the defaulting contractor.

The right to the assignment only arises where:

- an unpaid person is owed money for work carried out for or materials supplied to the defaulting contractor;

- there is money that is payable or will become payable to the defaulting contractor by the principal for work or materials that the defaulting contractor was engaged to carry out or supply under a contract; and

- the work carried out or materials supplied by the unpaid person are, or are part of or incidental to, the work or materials that the principal engaged the defaulting contractor to carry out or supply.

How does an unpaid person effect the assignment?

Judgment and debt certificates

To exercise the right of assignment, the unpaid person must firstly obtain a judgment against the defaulting contractor. This traditionally meant having a court or arbitrator give a judgment in favour of the unpaid person. Once a judgment has been received, the unpaid person must obtain a debt certificate for the amount owed. The unpaid person can apply to a court for a debt certificate.

The fact that the unpaid person must have obtained a judgment debt against the defaulting contractor means that the NSW Debts Act is rarely used. By the time the unpaid person obtains the judgment debt, it is unlikely that the principal will still owe the defaulting contractor any money which is the subject of the assignment.

However, the NSW Debts Act has been amended to allow a court to issue a debt certificate based on an adjudication certificate issued under the NSW Act.

Notice of claim

To make the assignment of the obligation to pay the debt under a debt certificate effective, an unpaid person must serve a notice of claim in an approved form on the principal.

What must a principal do when faced with a claim?

Receiving a notice of claim

When a principal is served a notice of claim, it must pay the money owed to the defaulting contractor to the unpaid person.

Failure to pay the debt entitles the unpaid person to start proceedings in court for recovery against the principal. However, the principal does have a right to defend any proceedings.

Does the principal owe any money to the defaulting contractor?

If there is no money payable to the defaulting contractor by the principal, the unpaid person has no right to assign its debt to the principal and the principal will have no obligation to pay the unpaid person.

CASE STUDY

West Tankers Pty Ltd v Scottish Pacific Business Finance Pty Limited[2017] NSWSC 621

Facts

- West Tankers Pty Ltd (West Tankers) supplied diesel fuel. Scottish Pacific Business Finance Pty Limited (Scottish Pacific) was a financier. The case was a contest to determine which of them was entitled to an amount paid into the District Court of NSW by a third party, the McConnell Dowell OHL Joint Venture (MDOJV).

- West Tankers supplied fuel to Ealwin Pty Ltd (Ealwin), who in turn, supplied to and invoiced the MDOJV. West Tankers then provided an invoice to Ealwin but it failed to pay.

- In 2009, Ealwin had entered into a facility agreement with Allianz Pty Ltd (Allianz) under which Ealwin sold to Allianz debts owed to it, including the debt owed by MDOJV which was transferred to Allianz ‘completely and unconditionally’. Allianz then assigned its rights under the facility agreement to GE Commercial Corporation Australia Pty Ltd (GE) who then gave notice of the assignment to MDOJV on 31 March 2016. GE then assigned its rights to Scottish Pacific on 3 May 2016.

- Meanwhile, West Tankers served a payment claim on Ealwin on 18 February 2017.

- On 17 March 2016, West Tankers applied for adjudication of its payment claim and served a payment withholding request on MDOJV under the NSW Act. MDOJV was then required to retain the money owed to Ealwin.

- On 11 April 2016, West Tankers obtained an adjudication determination which was filed as a judgment debt under the NSW Act on 26 April 2016. The NSW Debts Act provides that service of the notice of claim on MDOJV operated to assign to West Tankers the obligation to pay Ealwin. West Tankers served on MDOJV a notice of claim pursuant to the NSW Debts Act for the judgment debt on 5 May 2016.

- Scottish Pacific asserted that it was the legal owner of the Ealwin debt due to the legal assignment to it under the facility agreement perfected by GE’s notice of assignment to MDOJV on 31 March 2016. West Tankers claimed that, pursuant to the NSW Debts Act, it was entitled to the money as the assignee of the Ealwin debt.

Result

- The court ordered the moneys be paid to Scottish Pacific.

- The court found that the NSW Debts Act did not restrict Ealwin from lawfully dealing with its property, being the Ealwin debt, whether after the service of a payment withholding request or at all.

- By 31 March 2016, the debt owed by the MDOJV to Ealwin had been assigned to GE. Upon service of the notice of assignment, GE became the legal owner of the Ealwin debt, and Ealwin no longer had any interest, legal or beneficial, in it. From that date, Ealwin had no legal entitlement to payment.

- Even if the NSW Debts Act had operated to assign the Ealwin debt to West Tankers, that assignment would have occurred on 5 May 2016 which was in any event after the assignment of the Ealwin debt to GE. As the assignment to Scottish Pacific was effective and there was no assignment to West Tankers, the moneys should be paid to Scottish Pacific.

Other reasons for non-payment

Before making payment to the unpaid person, the principal should consider the following:

- If a binding assignment has already been made more than seven days before, the debt which ranks in priority must be paid first.

- If after 7 days from the date of service of the notice of claim there are other notices of claim that have been served in the same period, the principal must make pro rata payments.

- In making payments to the unpaid person, the principal must comply with the contract between the principal and the defaulting contractor and pay the unpaid person as payments become payable under that contract.

- A principal may be entitled to resist payment of the debt of an amount that exceeds 120 days wages or involves something moveable which would be practicable for the unpaid person to exercise a lien over.

- Proceedings for a debt cannot be taken more than 12 months after the debt becomes payable. A debt that is payable because of an assignment under the NSW Debts Act, becomes payable by the principal when it would have become payable to the defaulting contractor as if there had been no assignment.

Discharge notice

On assignment of a debt, a principal must make payments to an unpaid person until the principal receives a notice that fully discharges the debt, or the payments are no longer payable under the contract between the principal and the defaulting contractor, whichever occurs first.

An unpaid person must provide a discharge notice acknowledging payment of a debt, or part of a debt, if requested by the principal.

What are the contractor’s rights if not paid – how does a contractor enforce its rights?

If the principal does not pay a debt the subject of a notice of claim the unpaid person must sue the principal for the assigned debt. The principal may then defend the claim using any defence which it would have had against recovery of the debt by the defaulting contractor.