Chapter 21 The effect of proportionate liability on risk allocation

The proportionate liability legislation shifts the risk of a concurrent wrongdoer not being able to pay its portion of the plaintiff’s loss from the defendant to the plaintiff. Under the common law principle of joint and several liability, the plaintiff can sue the wealthiest concurrent wrongdoer for the full amount of its loss, even if on an apportionment basis the defendant is legally responsible for only a small fraction of the plaintiff’s loss. If the other concurrent wrongdoers are insolvent or impecunious, the defendant cannot obtain contributions from them and bears the entire responsibility for the plaintiff’s loss.

Practical consequences of proportionate liability – destabilising the contractual allocation of risk

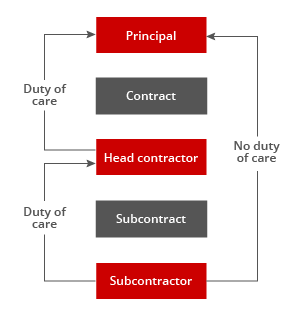

In construction projects, principals usually rely on the contractor as a single point of responsibility. Proportionate liability legislation destabilises such contractual arrangements, because, if the claim is an apportionable claim, the principal can only sue each concurrent wrongdoer for the proportion of the Principal’s loss each wrongdoer is legally responsible for.

For example, if a roof leaks because a subcontractor negligently waterproofed the roof, and the contractor negligently fails to detect the error when inspecting the subcontractor’s workings, the subcontractor and contractor will be concurrent wrongdoers. If the court finds the contractor was only 20% responsible, the plaintiff will only be able to claim 20% of the property damage and economic loss it suffered from the contractor. It will need to sue the subcontractor for the remaining 80%.

The destabilising effect of proportionate liability legislation is tempered by two factors:

- Proportionate liability only applies to apportionable claims, which are essentially claims of negligence (not relating to personal injury) or misleading and deceptive conduct in trade. Each wrongdoer must owe a duty of care to the plaintiff and have breached that duty of care, causing the same loss to the plaintiff. Courts have been slow to recognise that a person owes a duty to a plaintiff if the plaintiff has by contract agreed a detailed allocation of risks (see Owners Corporation Strata Plan 61288 v Brookfield Multiplex [2012] NSWSC 1219). This applies if the plaintiff contracted directly with the person, or if there is an intermediary in the contractual chain between the plaintiff and the person.

- In New South Wales, Tasmania and Western Australia, parties are considered to have contracted out of the proportionate liability legislation if their rights and obligations in contract differ from or are inconsistent with those provided in the proportionate liability legislation, even if they haven’t expressly stated that they do not intend to be bound by the relevant proportionate liability regime (see Perpetual Trustee Company Ltd v CTC Pty (No 2) [2013] NSWCA 58).

CASE STUDY

Commonwealth Bank v Witherow (2006) VSCA 45

Facts

- Mr Witherow guaranteed a bank loan to a company of which he was director.

- The company went bankrupt, and the bank called on the guarantee.

- Mr Witherow sought to engage the proportionate liability regime and to join his accountant to the legal proceedings, who he argued had failed to give proper advice about the company’s financial position before he signed the guarantee.

- The bank appealed the court’s decision allowing Mr Witherow to join his accountant.

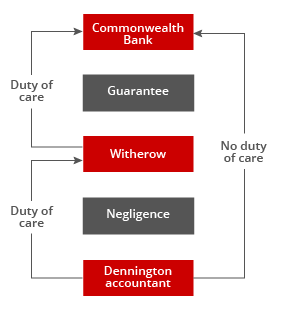

- The legal relationships of the parties are shown diagrammatically below:

Result

- The bank’s claim was not an action for damages, let alone an action for damages arising from a failure to take reasonable care – it was an application for performance of a guarantee. It therefore did not engage the proportionate liability regime.

- Whilst Mr Witherow’s accountant owed him a duty of care, it did not owe any duty of care to the bank.

The decision in Commonwealth Bank v Witherow illustrates the limited scope of proportionate liability legislation. A contractor and subcontractor will only be concurrent wrongdoers if the subcontractor owes a duty of care to the principal. The circumstances in which a subcontractor would owe a duty of care to the principal are limited as between sophisticated parties who have negotiated a contractual allocation of risk. The High Court held in Woolcock Street Investments Pty Ltd v CDG Pty Ltd that ‘the capacity of a person to protect him or herself from damage by means of contractual obligations is merely one — although often a decisive — reason for rejecting the existence of a duty of care in tort in cases of pure economic loss.’ ( See case study above: Woolcock Street Investments Pty Ltd v CDG Pty Ltd)

In the context of residential construction work, the High Court of Australia in Bryan v Maloney (1995) 182 CLR 602 has held that a builder owed a duty of care to a subsequent purchaser of a residential home many years after its construction. However, High Court rejected a subsequent case on near identical facts relating to a commercial construction, Woolcock Street Investments Pty Ltd v CDG Pty Ltd [2004] ). The decision, whilst not overturning Bryan v Maloney, identified that the conceptualisation of negligence in Bryan v Maloney had been superseded in Australia in subsequent cases. The court did not feel a need to overturn Bryan v Maloney, as liability for residential building defects is now largely dealt with by legislation in Australia (see chapter 14 – Building regulation)

In any event, a principal can shield itself against the practical effect of proportionate liability by obtaining an indemnity from the contractor that indemnifies the principal for losses or damages arising from a duty a subcontractor may owe to the principal (see Samways v WorkCover Queensland [2010] QSC 127).